Geopolitical risks, including trade wars, sanctions, and political instability, have a significant impact on global trade, directly affecting exporters worldwide. To stay competitive in international markets, exporters must be proactive in responding to these risks. For instance, in 2023, Mexico surpassed all other U.S. goods trade partners, while trade between Vietnam, the U.S., and China saw rapid growth. Meanwhile, European energy imports from Russia sharply declined, and imports of Chinese goods, like electric cars, rose dramatically. As these trade shifts reflect broader geopolitical tensions, exporters need to implement strategies to mitigate risks and adapt to the evolving global trade landscape.

Alongside these headlines, decision-makers in government and business have developed a new vocabulary. Between 2018 and 2022, the terms “decoupling,” “derisking,” “reshoring,” “nearshoring,” and “friendshoring” were used more than 20 times more frequently in business presentations[1]. At the same time, the number of new global trade restrictions has been constantly increasing from 650 new restrictions in 2017 to 3000 in 2023. How can this be understood?

Global Trade value (both goods and services) has gradually increased for all economies over the last 30 years. However, since 2017 the “global trade geometry” (in other words: trade relationship preferences) has been seriously shifting. Thus, McKinsey research institutes the new measure of “Geopolitical distance” has been implemented.

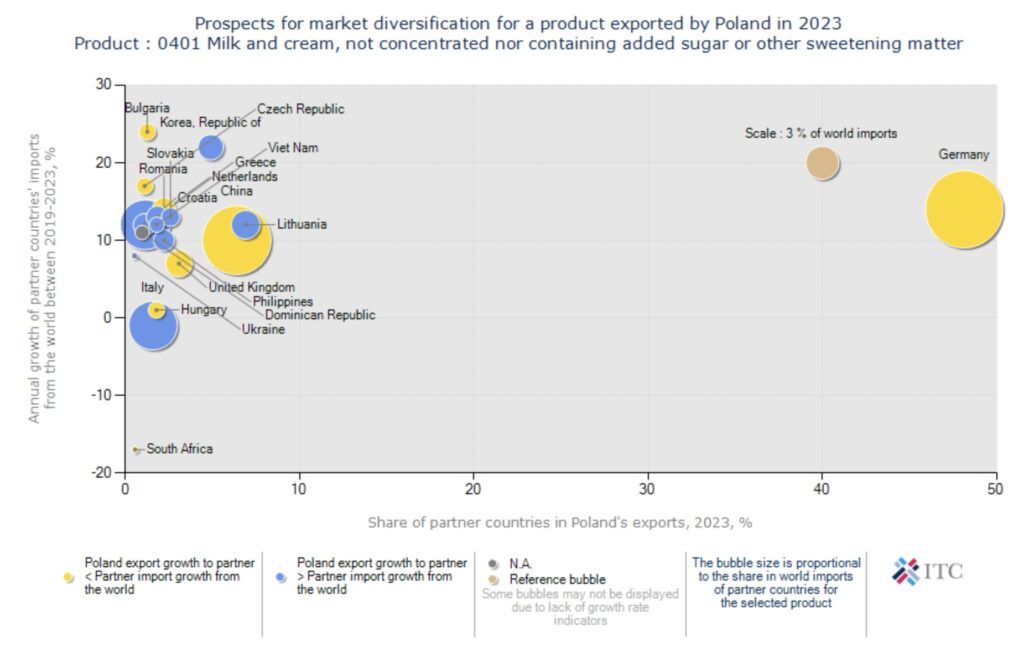

From our perspective, it’s critical to apply the “geopolitical distance” factor when companies are choosing a new market for their products or services [https://manatex.co/how-to-choose-the-right-export-market-for-international-expansion/]

Although researchers (e.g.McKinsey Global Institute) believe that trade in concentrated products binds geopolitically distant economies, it is clear that geopolitical distance between some countries (e.g. the USA and China) will increase in the coming years.

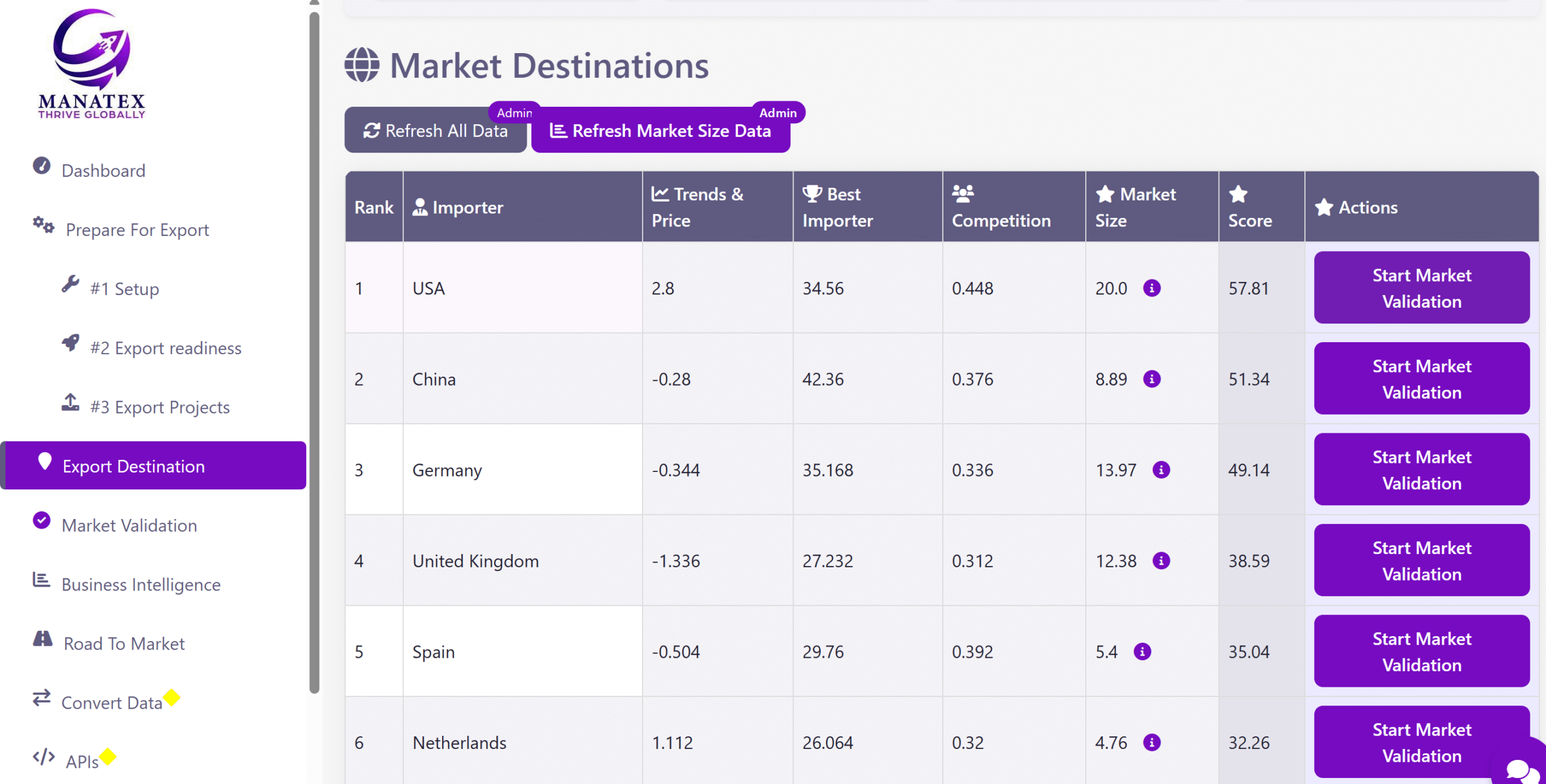

Trade reconfiguration isn’t at all finalized, it’s underway. For example, BRICS countries are trading more and more with each other. This is also important to keep in mind that some countries tend to stay towards the middle in the geopolitical range (e.g. Mexico, Brazil, India) and thus, trade over geopolitical distances (see picture #1)

Picture #1: Large Economies’ trade relationships vs geopolitical distance (source: McKinsey)

Under the situation of high uncertainty, companies, especially, the most vulnerable sector of SME exporters have to build their resilience in global trade. What can they do about it?

1)Maybe this sounds obvious but this is very important to stay “updated” with the situation and monitor the geopolitical trends and “distance” before making decisions on “risky” market penetration. Different reliable sources of information can be used in this case. We’re listing some of them:

-

- https://www.chathamhouse.org/topics/economics-and-trade

- https://worldview.stratfor.com/

- WEF – The global cooperation barometer

- Foreign Ministry websites

- https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker

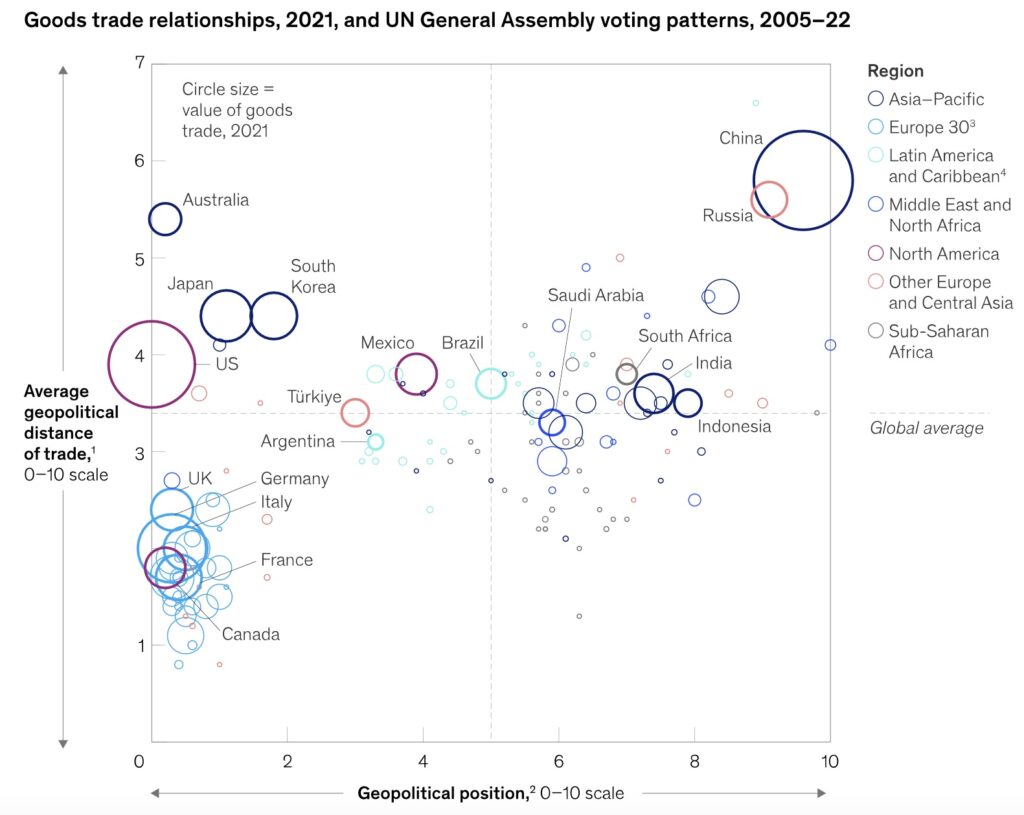

2)According to article[2], global trade is concentrated. The first kind of concentration is worldwide, in which two or three countries supply the majority of a given good. For instance, the majority of the world’s soybean exports originate from either Brazil or the United States (Picture #2). The second form, economy-specific concentration, makes up around 30% of global trade and occurs when countries purchase goods from just two or three supplier nations even though they have many options. Consider wheat: over 90% of the world’s wheat is produced in 15 nations, yet Turkey mostly imports its wheat from Russia and Ukraine. An intriguing fact about bananas is that, despite their production in many nations, Ecuador supplies 95% of Russia’s banana needs. This sort of concentration makes companies and even the whole nation (dependent on the export/import of a certain product) vulnerable.

Picture #2: Global creation and trade flows of soybeans, 2021, mln of tons (Source: McKinsey Global Institute).

What can exporters do about it? Although it often feels like it’s easier to export to the countries where the competitors are already present, we recommend looking for opportunities where the concentration is lower while geopolitical distance isn’t high. This will allow companies to build geopolitical resilience. Companies can check trade concentration using tools like www.trademap.org

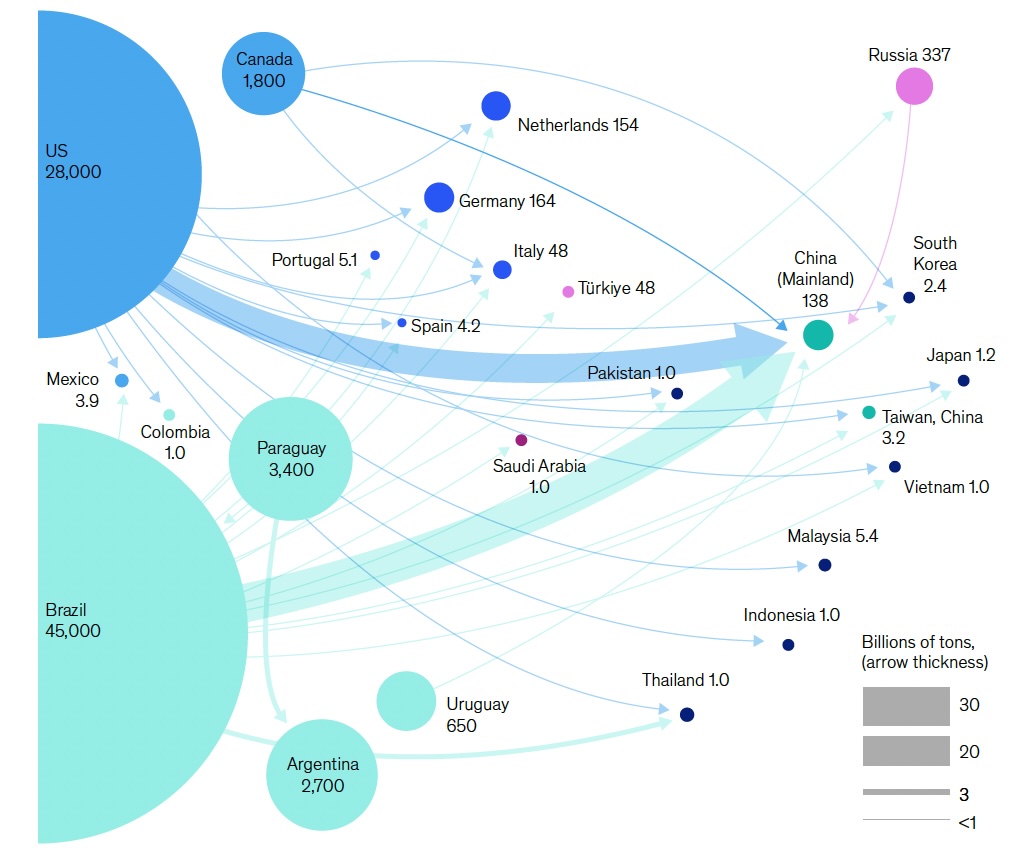

As an example, let’s look at Trademap analytics for milk products (HS Code 0401) produced in Poland (Picture #3).

Picture #3: Import of product exported from Poland in 2023, HS Code 0401: Milk and cream, not concentrated, not containing sugar (source: www.trademap.org)

This is clear that Germany imports almost 50% of milk exported from Poland. Although the geopolitical distance between these two countries is very low now, German companies mostly sell milk from Poland as a product for private labels in retail chains (e.g. Aldi, Lidl, etc) and don’t promote Polish brands on the German market. In some countries (e.g. South Korea) the import of milk produced in Poland isn’t high but it’s increasing. We recommend paying attention to this kind of trend.

[1] McKinsey Global Institute: “Geopolitics and the Geometry of Global Trade”